Fostering intercultural communication competence through virtual exchange

by Jodie Birdman

In 2020, many things that were previously unthinkable became part of daily life and other things which were routine became impossible. Here at Leuphana, that meant that online learning took a massive leap from a class-specific practice to ubiquity. Within weeks everything from lectures to conferences was digitalized. Within a year nearly all classrooms were equipped with cameras and microphones. Unfortunately, with this leap forward came the loss of a vital part of modern education – international study exchanges and semester abroad programs all but stopped.

But did they really?

I was also teaching at the time, and my class included international students. Many of them returned to their families either from necessity or worry. Normally this would have resulted in, at best, a pause in their studies. However, with the help of digital teaching and learning technology, they were able to continue regular, weekly participation in classes, group work, and assignments. Other instructors had similar experiences. When life gives you lemons, you make lemonade, and we at Leuphana realized that we had quite a lot of lemonade to offer! Could it perhaps be the answer to a long-standing problem?

For years the number of students who choose to go abroad has been sinking, as has the length of their time abroad. The barriers to studying or taking an apprenticeship abroad are many, including financial barriers, geo-political trends, family commitments, and personal reluctance to take such a big step. This was all true even before the pandemic. And yet, the emphasis on the importance of just such a big step has been growing in multiple fields. Governmental bodies such as the UN see exchanges as vital for learning and maintaining peace, businesses value international experience for the knowledge and skills it supports, and here in education we recognize the invaluable learning and relationship-building that takes place through such exchanges.

In the DigiCLIL project, we wanted to create a class where students could experience some of the benefits of a study abroad without leaving Lüneburg. In this way, we hoped to make international experiences more accessible to our students and provide a stepping stone to those considering a study abroad, but not yet convinced. We believe that thanks to digital innovation, a virtual exchange can provide that opportunity.

To do this, we first needed a few things.

- The technological hardware to create an international blended-learning experience

- The software to support this experience

- A course concept and syllabus

- International partner universities with whom we could carry out this project

- Students to take part

The hardware was there and ready. In December 2021 we began to work on the rest.

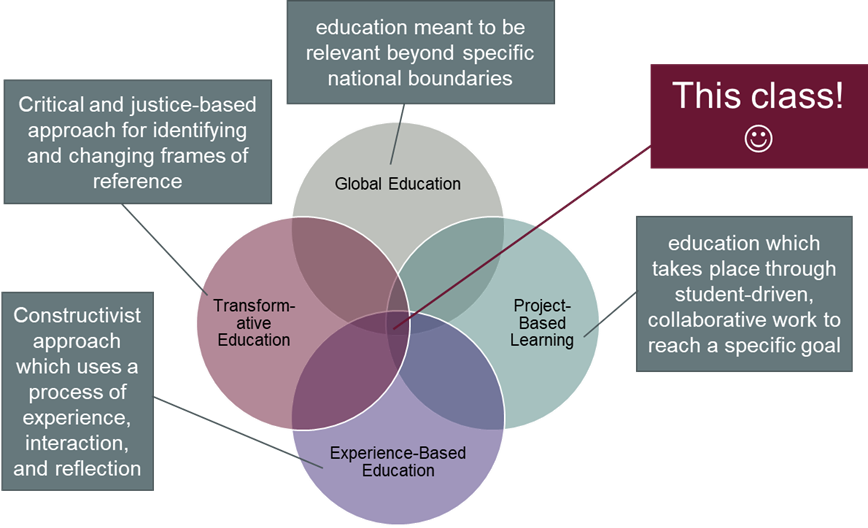

“Fostering intercultural communication competence” is a mouthful, and it is still easier said than done. Competence consists of knowledge, skills, and attitudes. These are best supported through student-centered learning activities. According to Kuriscak and Kirkwood (2018), Kolb & Kolb’s (2012) experience-based-learning framework provides the ideal routine of starting with the students’ existing knowledge, engaging with new information and experiences, and then reflecting in order to integrate these new findings with their previous understanding. Further support from Byram (2020) suggests that intercultural communication competence is best developed through collaborative work on a common goal, provided there is adequate facilitation and support. It was clear that we would need to create a syllabus where through virtual exchange, the students would work on a collaborative project.

The next challenge was to come up with a topic that would be interesting to students at Leuphana and to students at other universities around the world, regardless of their area of study. The simplest answer was to let the students choose, but that is not the simplest thing to plan. We decided that we would use an overarching concept which is in use internationally and which embeds nearly all possible topics in the humanities, social, and natural sciences: The 2030 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Using this as a guide, the students could choose a specific phenomenon. Then, they could investigate how it is embedded in the social, economic, cultural, and environmental systems where they are and, through comparison, learn about each other. Then, they would take that knowledge and turn it into a blog entry in order to share their learning with others. With that concept, we developed a syllabus.

Global Education: Viebrock (2015), Project-Based Learning: Kolmos (2009), Experience-Based Education: Kolb and Kolb (2012) Transformative Education: Mezirow (1997),

We often say that this class is more about the journey than the destination. The experiences the students have interacting with each other and with their international partners are invaluable. Every semester we are excited to see what sustainability solutions they choose to investigate, and what they learn. Each session consists of subject content on intercultural communication, global citizenship, culture, and sustainability and a working session with videoconference assistance. The students regularly write reflections about their experiences and document their project work as they go. They also give each other feedback on their work so that the groups also build a system of mutual, critical support.

We are convinced from our interactions with them that they are indeed going through a holistic learning process which includes becoming more reflective, more aware of their own way of interacting, more sensitive to others, and more resilient to the challenges that come with collaborative project work. However, our own conviction is not a particularly scientific method. We want to have research-based evidence that this method is indeed effective. We were aware that to achieve the goals of the course, we would need to build a particularly safe environment for the students to try new things and explore their reactions. It was imperative that whatever we did, it must not violate their trust. Therefore, as we designed the activities we ensured that they were not only evidence-based, but also resulted in a documentation of the students’ learning process in a way that we could analyze to evaluate the curriculum and delivery.

At the same time we did all this, we also worked constantly to recruit collaboration partners and build a platform where this would be possible. Finding instructors who were interested was relatively easy. Gaining institutional permission and coordinating the logistics was less so. Finding ways to solve organizational challenges from timing to assessment to information sharing was another story that deserves its own blog. Likewise, we found that aside from time zones, semester schedules, and university regulations, we also had differences in data security laws to contend with. We were experiencing, in a way, exactly what our students would be doing. We were learning about a specific solution and the complexity of our and our partners’ contexts.

Our collaboration is moving forward with partners at universities in several countries. This semester we are working with the university Trabzon in Turkey, and the students are off to a good start. We learned many things in the first delivery of our class, and we learned even more from the students who took part. Our original concept of introducing German bachelor students to their first international experience was perhaps naïve. We learned that our students bring a richness of experience far beyond anything we could anticipate, and we are humbled to also be able to learn from them.

Last semester our class had two project groups. One chose to explore food waste and hunger in Lüneburg, Germany and Colombo, Sri Lanka. The other investigated sexual health education in Hamburg, Germany and Dublin, Ireland. We look forward to publishing their work soon.

Publication bibliography

- Byram, Michael (2020): Teaching and assessing intercultural communicative competence. Revisited / Michael Byram. Second edition. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Kolb, Alice Y.; Kolb, David A. (2012): Experiential Learning Theory. In Norbert M. Seel (Ed.): Encyclopedia of the sciences of learning. New York: Springer (Springer reference), pp. 1215–1219.

- Kolmos, Anette (2009): Problem-Based and Project-Based Learning. In Ole Skovsmose, Paola Valero, Ole Ravn Christensen (Eds.): University Science and Mathematics Education in Transition. Boston, MA: Springer US, pp. 261–280.

- Kuriscak, Lisa M.; Kirkwood, Kelly J. (2018): The Role of Individual Factors in Students‘ Attitudes toward Credit-bearing Predeparture Classes. In Cristina Sanz, Alfonso Morales-Front (Eds.): The Routledge handbook of study abroad research and practice. 1st. London: Routledge (Routledge handbooks in applied linguistics), pp. 493–508.

- Mezirow, Jack (1997): Transformative Learning. Theory to Practice. In New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education 1997 (74), pp. 5–12. DOI: 10.1002/ace.7401.

- Viebrock, Britta (2015): How Global Education Could Be Inspired by the CLIL Discourse – and Vice Versa. In Christiane Lütge (Ed.): Global education. Perspectives for English language teaching. Zürich: Lit (Fremdsprachendidaktik in globaler Perspektive, Bd. 4), pp. 39–56.