Hello! We are Malou, Feisal and Nayama from the University of Leuphana, Germany, Aryanna, Diego, Peter, Lamia and Conner from the University of Florida, USA and Junaid from the Universidade Estadual Paulista, Brazil. We have been working together in the framework of our seminar culture, sustainability and intercultural communication virtual exchange project.

Fun fact: the majority of this project was written on trains.

Starting the journey – Malou, Feisal, Nayama

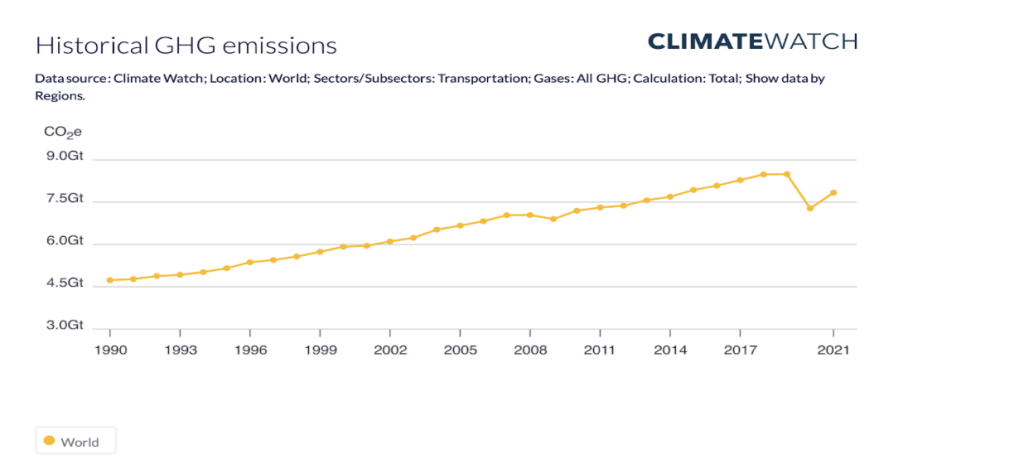

Every day, we all have places to be-work, school, or university. But how do we get there? Do we drive, take public transports, bike, or walk? Surprise, surprise… these are all questions related to mobility. These choices shape our routines and impact the environment. The transport sector contributes nearly 20% of total greenhouse gas emissions (World Economic Forum, n.d.), affecting air quality, land use, and ecosystems. Addressing these issues requires more sustainable transportation.

The United Nations define sustainable transport as safe, affordable, accessible, and environmentally friendly. Inspired by this, our multinational team explored how universities promote sustainable transport. Through surveys, interviews, and discussions, we uncovered how infrastructure, culture, and policies influence mobility—and how different institutions tackle this challenge.

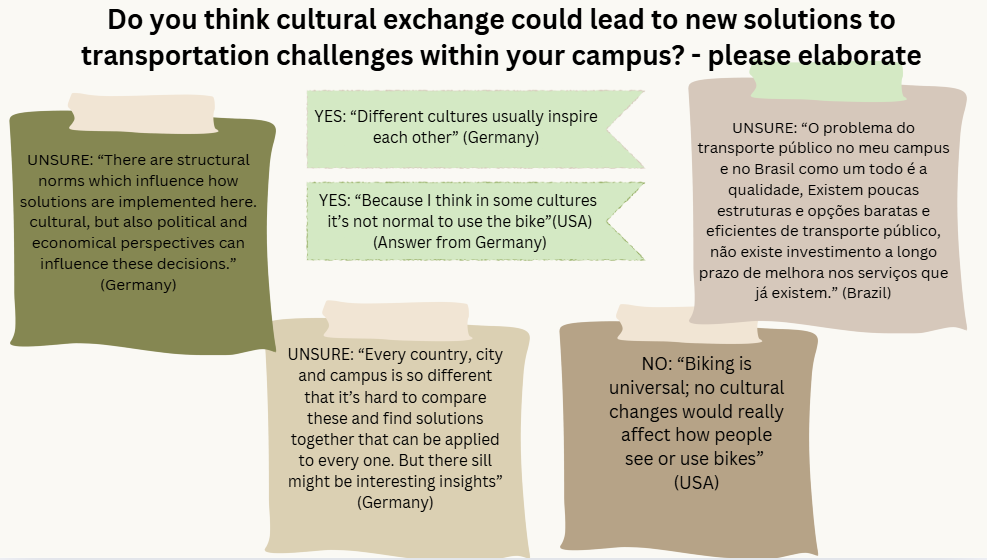

We found significant variations. Some universities prioritize biking and public transport, while others struggle with accessibility and infrastructure. Government policies, incentives, and cultural attitudes shape these differences. Our findings reveal how much we can learn from each other’s successes and challenges.

In this blog, we’ll share what we’ve learned and why it matters—not just for getting to class, but for building a better future. Small changes in how we travel can make a big difference.

Navigating Lüneburg – Nayama

As I sit on the train to Hamburg courtesy of the ever-reliable Deutsche Bahn (German railway), writing this blog entry, I find myself reflecting on the different modes of transportation I rely on, including a ferry on one occasion, to get to my university. Through my train window, I see factory smoke curling up, a somber reminder of the price we pay everyday for our lifestyle. Yet, I feel grateful to reduce my impact in small ways, like many students at Leuphana University wh0 bike or take public transport. The campus is compact (0.189 km²) with 10,000 students, making sustainable mobility viable. The city itself is only 70.38 km² (Zahlen, Daten, Fakten, n.d.).

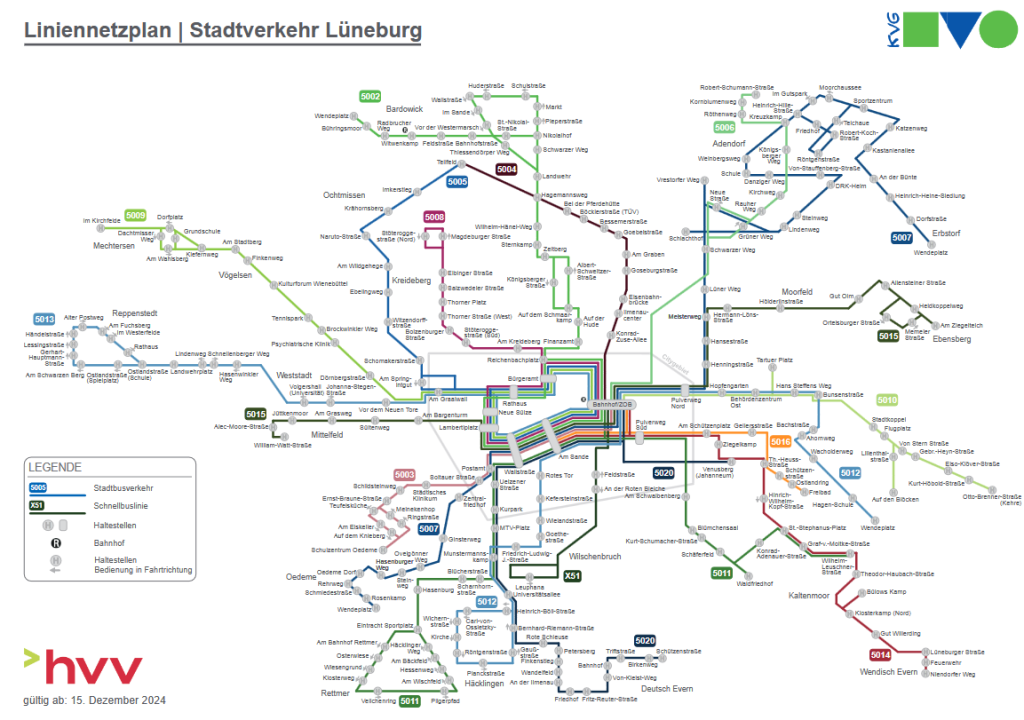

It makes me think of how Luneburg’s urban planning fosters bike-friendliness, walkability, and bus

connectivity. The university employs “push” factors (restrictions) such as limited vehicle access, bollards, and decentralized parking to discourage car use (Leuphana Nachhaltigkeitsbericht, 2022) (Mobilität, 2024).

Meanwhile, “pull” factors (incentives) include a Semester ticket, e-bike rentals (free for half an hour), charging stations, car-sharing options, bike repair stations on campus providing greener alternatives (Leuphana Nachhaltigkeitsbericht, 2022) (Mobilität, 2024).

It makes me wonder if this is influenced by Germany positioning itself as a pioneer in sustainability. National sustainability efforts, like the Deutschland ticket (affordable public transport) (The Deutschland-Ticket (n.d.)) and the National Cycling Plan (increasing bike use across the country) (National Cycling Plan 3.0. (n.d.)) probably influences Leuphana to implement mobility strategies that align with national goals. Lüneburg also benefits from the National Urban Mobility Policy (NUMP), which, supported by international frameworks, aims to develop integrated and inclusive mobility policies that align with the SDGs. It integrates sustainable transport strategies through data-driven planning, stakeholder engagement, and capacity-building activities (Changing Transport, 2020). Such efforts showcase how policy shapes student mobility choices.

This reminds me of yesterday’s chat with my friends about how the right systems can help make sustainable choices easier for everyone.

Navigating Gainesville – Malou

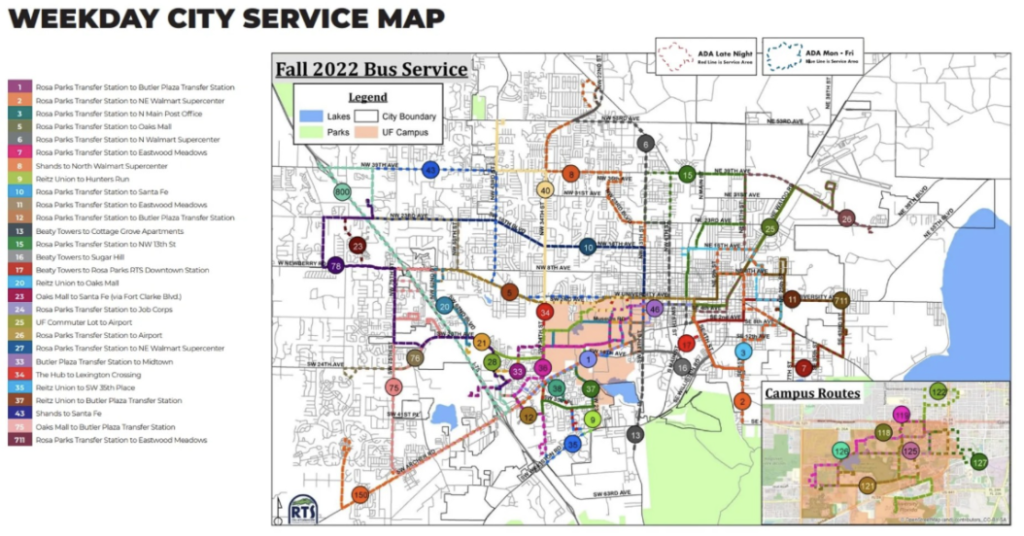

One of my friends shared their experience at the University of Florida, which, while different from my experience in Germany, shares some common themes. The UF campus is much larger than Leuphana, with a population comparable to that of Lüneburg. With more than 60,000 students in a city of 145,000 inhabitants, the campus plays an important role in Gainesville’s infrastructure. Getting from one seminar to another can be a challenge – not surprising when you consider that the main campus alone covers more than 8 km² and has over 1000 buildings (UF Facts n.d.). Recently, new crosswalks and pedestrian signage have made the campus more walkable, and electric scooters are available for rent, which can be used on the designated bike lanes (Alternative Transportation – TAPS, n.d.). This has even led some students to describe a „moped culture“ (Survey conducted, 2024), with many buying scooters to get from one class to another more quickly, as walking would take much more time due to the large distances.

But there is more: Gainesville offers 48 free bus lines for students, supported by real-time tracking via an app, making it easier to plan trips. However, cars are still a popular choice, despite frequent overcrowding in parking lots, many of which are reserved for staff. Students often use discounted car-sharing options instead.

In addition, future budget cuts could result in the removal of 36 buses (Williams, 2024), potentially making the system less reliable and less frequent. Given that about 76% of UF-students live off-campus (University of Florida Housing, 2020, p.2), this uncertainty may push them toward the convenience of personal vehicles instead. Nevertheless, UF, like Leuphana, is striving to implement sustainable transportation options, by offering the mentioned incentives, which are less costly in comparison to unsustainable transportation methods. Those can be argued to function as pull-factors in similar ways to the ones in Lüneburg.

Hearing about their experience made me curious about how mobility and sustainability are approached in the global south. For example, are there similar efforts to balance environmental goals with practical access to transportation in Brazil?

Navigating Presidente Prudente – Feisal

A friend from Brazil explained how things differ in comparison to Germany and the USA. Brazil heavily relies on fossil fuels, despite its 2012 National Urban Mobility Plan aimed at reducing environmental and socioeconomic costs. Transportation was also included in the constitution as a “social right”. Yet, public transport is underfunded, relying mainly on user tariffs that disproportionately affect low-income populations. Metro and Bus Rapid Transit expansions have improved accessibility, and ride-sharing apps offer affordable alternatives to taxis.

At the UNESP in Presidente Prudente, mobility is particularly challenging. Covering 0.41 km2 and serving 227,072 students, it is larger than UF and Leuphana. Public transport is unreliable, and the university offers no incentives for sustainable mobility. As a result, most students rely on private cars. Limited infrastructure and awareness further hinder sustainable choices.

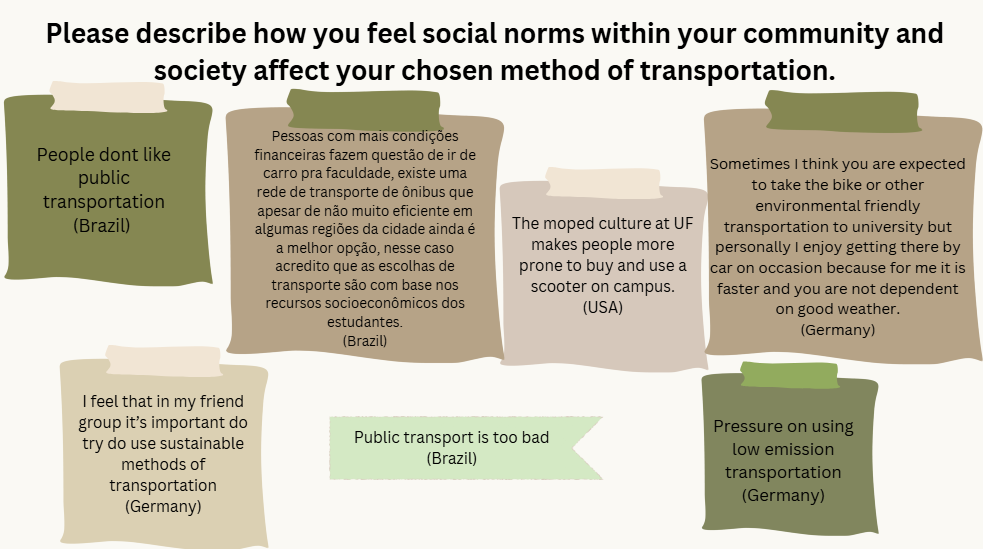

Navigating Student Transportation Choices (Survey Insights) – Nayama

As I compared my discussion with my friends across the different universities, I realized that policy and infrastructure play a key role in mobility choices. What if we go a step further? Is it also influenced by personal habits and cultural perspectives? A survey of 55 students across three campuses showed that while many care about sustainability, practical factors like time and cost also shape their choices. Distance matters most—since most live within a mile, walking (38.2%) is the go-to option. Even those farther away prefer buses, trains, bikes, or e-scooters over cars. Students pointed out barriers like poor infrastructure, safety concerns, and limited public transport, but surprisingly, bad weather wasn’t a big issue—they simply adapted with umbrellas and rain jackets. Most students (74.5%) walk on campus, highlighting the need for pedestrian-friendly campuses.

Quite surprising was the mixed attitude toward sustainability itself. While nearly half (49.1%) use sustainable transportation daily, only 58.5% considered sustainability very important in their decisions, with some even ranking it as unimportant. Leuphana showed the most divided opinions, whereas students at UF and UNESP generally rated sustainability as somewhat important.

Students at Leuphana and UF rated their universities’ sustainability efforts as somewhat effective, while UNESP students leaned toward ineffective or neutral. Many respondents were unsure if their university had formal sustainability goals, highlighting a lack of awareness.

Navigating from Lüneburg to Gainesville to Presidente Prudente – Feisal

Through these discussions, I noticed both similarities and differences in mobility challenges. Public transport plays a vital role but remains unreliable in many places. Private cars and ride-sharing apps dominate Brazil and Florida, while biking and public transport incentives encourage greener choices in Lüneburg.

Sustainable transport depends on policy, infrastructure, and accessibility. While Leuphana and UF implement bike-sharing, electric vehicles, and free shuttles, UNESP lacks similar support due to financial constraints. Yet, all three universities face common struggles—such as inadequate infrastructure and continued reliance on fossil fuels.

Collaboration can drive change. If universities share best practices, they can learn from each other’s successes. Expanding public transit investment, improving walkability, and fostering institutional collaboration could accelerate sustainable mobility worldwide. The choices we make today shape tomorrow’s Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

Our journey comes to an end – Nayama

As my train reaches Hamburg Central Station, I reflect on global mobility and sustainability. From Lüneburg’s bike-friendly streets to Gainesville’s tech-driven transit and Presdidente Prudente’s expanding metro, it’s clear that every city is working toward greener transport in its own way.

What strikes me most is the power of individual choices. At Leuphana, sustainable options are encouraged, making green choices easier. But as my friends and I discussed, no system is perfect—infrastructure gaps, policy limitations, and convenience factors all shape behavior. Learning about other universities’ efforts gives me hope. Every step forward, no matter how small, makes a difference.

While the challenges are global, so are the solutions. By sharing ideas and learning from each other, we can create change that extends far beyond our own campuses or cities. In the end, it’s about choosing to care. Choosing to walk instead of drive, cycle instead of taking a car, or advocating for better public transit. These small choices add up. As students, communities, and global citizens, we have the power to make sustainable transport the norm.

Let’s keep moving forward–together

Editing: Nayama, Feisal and Malou

Sources:

Alternative Transportation – TAPS. (n.d.). Last visited on 02.03.2025, from [https://taps.ufl.edu/alternative-transportation/]

Bing Maps. (n.d.). Retrieved from [https://www.bing.com/maps?q=leuphana+size&FORM=HDRSC7&cp=53.228898%7E10.401099&lvl=17.1]

Brüggen. (2024). Mobilität. Leuphana Universität Lüneburg. Retrieved from [https://www.leuphana.de/universitaet/nachhaltig/mobilitaet.html]

Changing Transport. (2020, December 2). National Urban Mobility Policies and Investment Programmes (NUMP) Guidelines – Changing Transport. Retrieved from [https://changing-transport.org/publications/national-urban-mobility-policies-and-investment-programmes-nump-guidelines/]

Delgado, F. C. M., & Bezerra, B. S. (2021). Subsidies for public passenger transport in Brazil—a sustainable mobility issue. Latin American Journal of Management for Sustainable Development, 5(2), 95-109.

History. (2024, June 30). Leuphana University Lüneburg. Retrieved from [https://www.leuphana.de/en/university/history.html]

Leuphana Universität Lüneburg. (2022, April). Nachhaltigkeits-Bericht 2022. Retrieved from [https://www.leuphana.de/fileadmin/user_upload/uniprojekte/Nachhaltigkeitsportal/Nachhaltigkeitsbericht/files/2022_Leuphana_Nachhaltigkeitsbericht.pdf]

Mobilität. (n.d.). Leuphana Universität Lüneburg. Retrieved from [https://www.leuphana.de/universitaet/nachhaltig/mobilitaet.html]

National Cycling Plan 3.0. (n.d.). BMDV – National Cycling Plan 3.0. Retrieved from [https://bmdv.bund.de/SharedDocs/EN/Articles/StV/Cycling/nrvp.html]

NUMP. (n.d.). Lüneburg. Retrieved from [https://www.hansestadt-lueneburg.de/bauen-und-mobilitaet/mobilitaet/nump.html]

Survey conducted (2024). Retrieved from [https://docs.google.com/forms/d/1_r4yVbrxTiA9BhzbpXNJFccnJSf8IJyxo69_-JJlnG8/edit]

The Deutschland-Ticket. (n.d.). Retrieved from [https://int.bahn.de/en/offers/regional/deutschland-ticket]

UF Facts. (n.d.). Ufl.edu. Last visited on 02.03.2025, from [https://news.ufl.edu/for-media/uf-facts/]

United Nations. (n.d.). Mobilizing Sustainable Transport for Development. Retrieved from [https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/content/documents/12453HLAG-ST%20brochure%20web.pdf]

University of Florida Housing. (2020). University of Florida Housing Campus Master Plan, 2020-2030 Data & Analysis. Retrieved from [https://facilities.ufl.edu/wp-content/uploads/plan/2020-2030/data/Housing%20DandA%202020.pdf]

Williams, K. (2015, April 15). Proposed RTS cuts could impact future Gainesville, UF climate action plans. The Independent Florida Alligator. Retrieved from [https://www.alligator.org/article/2024/04/proposed-rts-cuts-could-impact-future-gainesville-uf-climate-action-plans]

World Economic Forum. (2022, June). Green transport and cleaner mobility are key to meeting climate goals. Retrieved from [https://www.weforum.org/stories/2022/06/green-transport-and-cleaner-mobility-are-key-to-meeting-climate-goals/]

Zahlen, Daten, Fakten. (n.d.). Lüneburg. Retrieved from [https://www.hansestadt-lueneburg.de/rathaus/zahlen-daten-fakten.html]

Photo references:

1. Climate Watch. (n.d.). GHG emissions by region and sector. Climate Watch Data. Retrieved from [https://www.climatewatchdata.org/ghg-emissions?breakBy=regions&end_year=2021§ors=transportation&start_year=1990]

2. HVV Plan. (n.d.). Retrieved from [Stadtverkehr Lüneburg – schematisch]

3-8, 13-14: Produced by the project work.

9. NUMP. (n.d.). Lüneburg. Retrieved from [https://www.hansestadt-lueneburg.de/bauen-und-mobilitaet/mobilitaet/nump.html]

10. City of Gainesville. (2023, August 13). Gainesville’s RTS map with current routes as of July 28, 2023. The Gainesville Sun. Retrieved from [https://eu.gainesville.com/story/news/local/2023/08/13/gainesville-residents-concerned-over-elimination-of-campus-rts-routes/70463102007/]

11. UF Perks. (n.d.). RTS: UF students can ride RTS public transportation fare-free by presenting their Gator 1 card. [Photograph]. UF Perks. Retrieved from [https://ufperks.wordpress.com/transportation/]

12. UNESP. (n.d.). Retrieved from [https://www2.unesp.br/]

References

Brüggen (2024). Mobilität. Leuphana Universität Lüneburg. https://www.leuphana.de/universitaet/nachhaltig/mobilitaet.html

Leuphana Universität Lüneburg. (April 2022). NACHHALTIGKEITS-BERICHT 2022. In NACHHALTIGKEITS-BERICHT. https://www.leuphana.de/fileadmin/user_upload/uniprojekte/Nachhaltigkeitsportal/Nachhaltigkeitsbericht/files/2022_Leuphana_Nachhaltigkeitsbericht.pdf

Survey conducted (2024) https://docs.google.com/forms/d/1_r4yVbrxTiA9BhzbpXNJFccnJSf8IJyxo69_-JJlnG8/edit

The Deutschland-Ticket. (n.d.). https://int.bahn.de/en/offers/regional/deutschland-ticket

National Cycling Plan 3.0. (n.d.). BMDV – National Cycling Plan 3.0

NUMP. (n.d.). Lüneburg. https://www.hansestadt-lueneburg.de/bauen-und-mobilitaet/mobilitaet/nump.html

Changing Transport. (2020, 2. Dezember). National Urban Mobility Policies and Investment Programmes (NUMP) Guidelines – Changing Transport. https://changing-transport.org/publications/national-urban-mobility-policies-and-investment-programmes-nump-guidelines/

history. (2024, 30. Juni). Leuphana University Lüneburg. https://www.leuphana.de/en/university/history.html

Bing Maps. https://www.bing.com/maps?q=leuphana+size&FORM=HDRSC7&cp=53.228898%7E10.401099&lvl=17.1

Zahlen, Daten, Fakten. (o. D.). Lüneburg. https://www.hansestadt-lueneburg.de/rathaus/zahlen-daten-fakten.html

https://www.weforum.org/stories/2022/06/green-transport-and-cleaner-mobility-are-key-to-meeting-climate-goals/

Mobilität. (o. D.). Leuphana Universität Lüneburg. https://www.leuphana.de/universitaet/nachhaltig/mobilitaet.html

Delgado, F. C. M., & Bezerra, B. S. (2021). Subsidies for public passenger transport in Brazil-a sustainable mobility issue. Latin American Journal of Management for Sustainable Development, 5(2), 95-109.

https://www.uber.com/global/en/r/cities/presidente-prudente-sp-br/

https://www.international.unesp.br/#!/life-at-unesp/foreign-student-guide/.