Marlon Nnamocha, Kana Casas and Egisona Qosja

Trigger Warning: This Blog article discusses themes of addiction, recovery, and environmental challenges, drawing inspiration from Alcoholics Anonymous’s framework. Reader’s discretion encouraged.

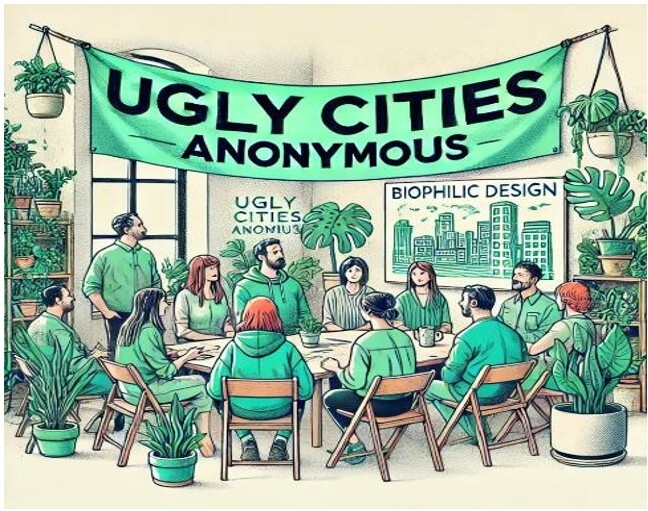

Welcome to Ugly Cities Anonymous, where we’ve all gathered to admit that, yes, our cities are often a far cry from the verdant, leafy places we crave. Urban deserts, towering glass facades, and green spaces that feel more like afterthoughts—if only our cities knew how to show their true colors! But fear not, fellow urbanites, because there’s hope on the horizon. Breaking the Cycle explores how biophilic design—our city’s version of rehab—can help cities reconnect with the natural world.

Like any good support group, our journey begins with acknowledging the problem: despite the hustle and bustle, our cities often lack that one thing that sustains both our bodies and minds—nature. Biophilia, the deep-rooted human connection to the natural world, offers a remedy. It’s not just about planting a few trees or installing a rooftop garden; it’s about rethinking urban spaces from the ground up, seeding sustainability, cultural identity, and green innovation into every street corner and high-rise.

But don’t worry, we’re not in this alone. Alongside us, there are a few senior members, who have already begun their recovery. Our friends from Lüneburg (Germany) and Gainesville (USA) are here to help guide us on this journey, sharing their stories of how they are turning their cities around. For decades, city planning prioritized cost-cutting, car-friendly design, and large apartment buildings, focusing on function over beauty and leaving cities feeling lifeless and disconnected from nature (Ellis 2019). But examples like Lüneburg’s climate-neutral campus and Gainesville’s nature-infused healthcare spaces show that change is possible.

Lüneburg

Dear Ugly Cities Anonymous, I am very excited to tell my story! I am sure we can all better ourselves, and I want to speak to you about what I achieved through city planning and hard work. I will also share my problems with you; nobody is perfect, but we should strive to become better for ourselves, the environment, and all our inhabitants.

My strength lies in biophilic design, as demonstrated by the iconic Leuphana University main building. While much of me has grown in harmony with nature for over a thousand years, part of me has taken a different path. What began as a modest teacher-training college has transformed into a sustainability-driven university, marked by Daniel Libeskind’s bold architecture. Some celebrate this as innovation, while others argue it clashes with my historic character (Trenkamp 2010). Still, I embrace my transformation and I’ve brought a little virtual tour of it for you—feel free to look around and experience its beauty! https://virtual-tour.web.leuphana.de/en/start/.

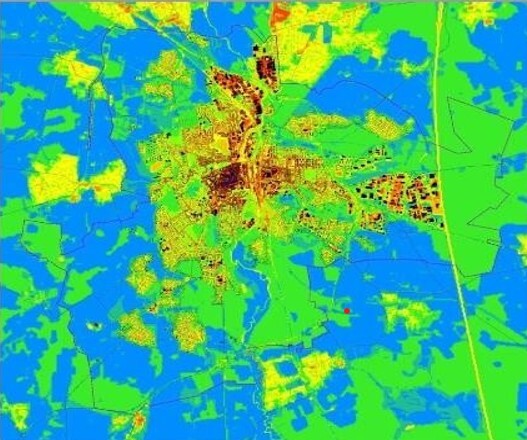

As you can see, the main building has a green roof covered with grass and floor-to-ceiling windows that flood the interior with natural light. I have also invested in solar energy, reducing my carbon footprint (Opel et al. 2017). I achieved a climate-neutral energy balance and received the sustainability award in 2023 (Zühlsdorff 2023). However, I still have flaws. For instance, my center, Am Sande, lacks many trees and becomes uncomfortably hot in the summer due to the absence of shade. This is problematic because excessive heat can negatively affect my inhabitants. However, incorporating biophilic designs, such as adding more vegetation, could help address this issue by reducing urban heat, improving air quality, and enhancing mental well-being (GEO-NET Umweltconsulting GmbH 2019).

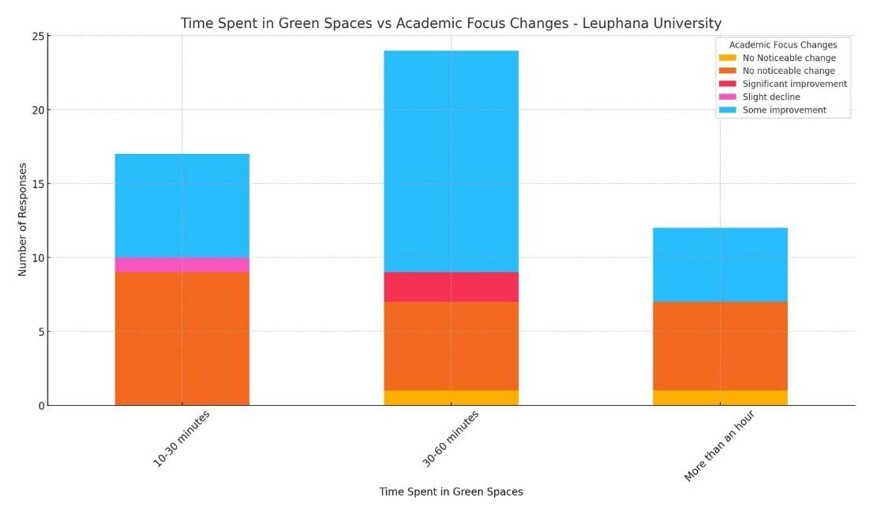

A recent survey carried out at Leuphana University revealed that spending time in nature helps students feel more relaxed and improves their mental and physical well-being (Nnamocha 2024). Most of them noticed health benefits, while only a few saw no change. Similarly, the majority believe biophilic architecture enhances urban environments, though some remain uncertain.

Lastly, I’d like to share a fascinating insight from this study. As you can see here, the students reported different changes in academic focus, compared to how much time they spend in green spaces. We noticed that around the board people felt either no improvement or some improvement, while those spending 30–60 minutes in nature reported the most significant benefits. Interestingly, none of the students in the sample reported spending less than 10 minutes outside!

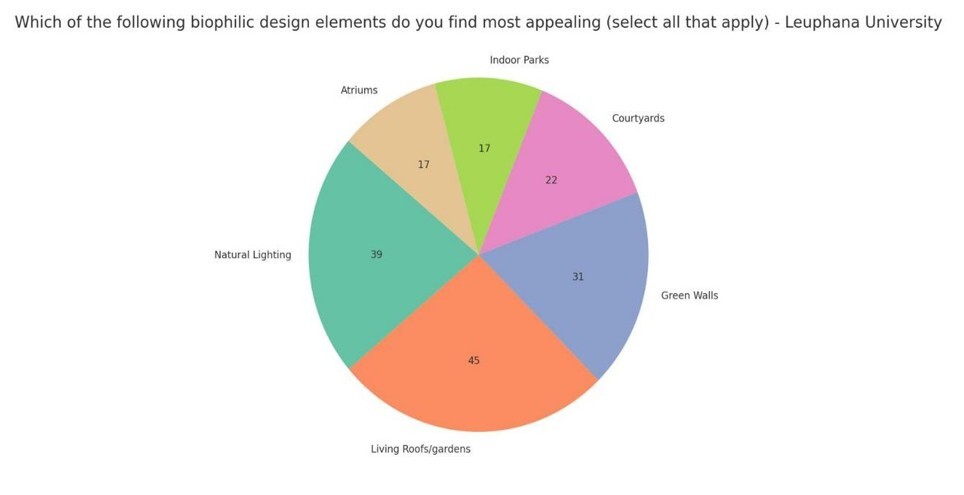

I’ll end my monologue now with a nice picture for you, dear ugly cities, to look at. My students shared which biophilic elements they found most appealing. Feel free to pass around and take a closer look!

Now I am giving the ball to Gainesville

Gainesville

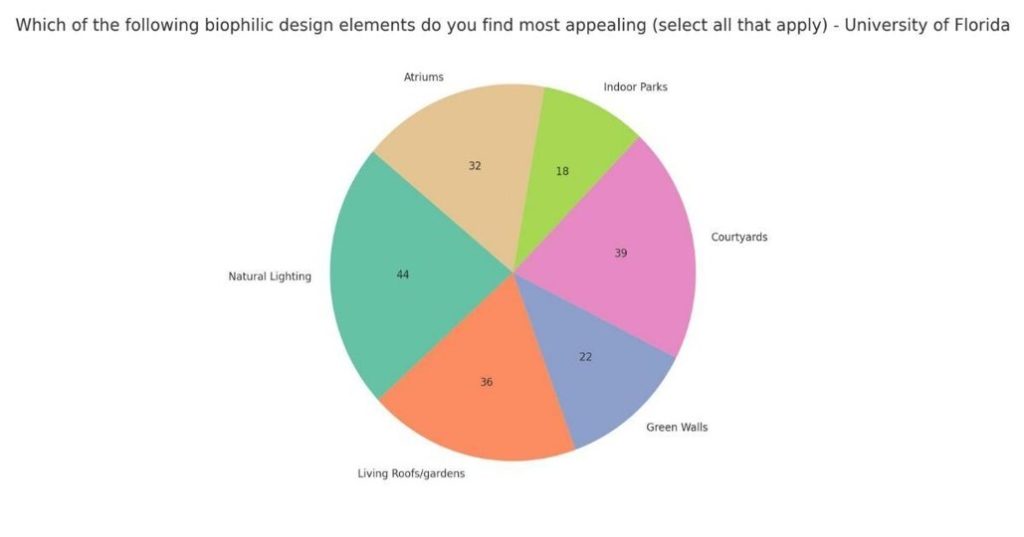

Thank you, Lüneburg. I saw the same effects as you! 26 out of 52 students at the University of Florida reported a significant positive impact on physical relaxation and health when spending time close to nature. While 22 felt some and 4, had no impact. Additionally, 44 students think biophilic architecture can improve urban landscapes, with 8 being not sure. I also brought the same chart as Lüneburg, a funny coincidence, but made by my students. Also, feel free to pass around.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

Now as for me, I’m proud of integrating biophilic design in the UF Health Shands Children’s Hospital. As one of the leading pediatric medical centers in Florida, this hospital plays a crucial role in advancing healthcare and research. If you look inside, you can see plants and pictures of animals on the walls, creating a warm, welcoming space for young patients. I even brought a little video, where children talk about the hospital! https://youtu.be/sUlYUp9cCl8.

For my people, it promoted well-being and impacted the community’s connection to nature. We found that biophilic environments reduce stress and improve mental health (McGee & Marshall-Baker 2015). This ultimately benefits my dear residents, making me more livable (Index Methods and Sources – AARP Livability Index, n.d.)!

Also, I want to add that my approach differs from Lüneburg’s not just in purpose but also in cultural context. In Germany, sustainability efforts often intertwine with historic preservation, blending old and new, while I have more flexibility to reshape my spaces. That’s why it was easier for me to redesign a children’s hospital than for Lüneburg to secure funding for a big, bold university project. Both of us are surrounded by nature, but while Lüneburg integrates green spaces into its urban core, I tend to preserve mine in parks and reserves just outside my city limits.

A big applause for our senior members and previously ugly cities!

I also want to applaud you, dear participants of Ugly Cities Anonymous, for being brave and willing to change. The numbers shared by our senior members show that people feel better when surrounded by nature. From improved focus to physical relaxation, the statistics clarify that biophilic design isn’t just a theory—it’s a proven way to enhance well-being in our cities. Lüneburg showed us how sustainability can blend with history, while Gainesville highlighted its impact on healthcare. Together, they proved that no matter the setting, nature can transform urban spaces for the better.

Why Mental Health Should Be at the Core of Urban Recovery?

Let’s be real for a second. Living in a city can be tough on the mind. The constant noise, the rush of people, the never-ending sea of grey. It’s no wonder urban residents are more likely to experience anxiety, depression, and burnout. And yet, the solution to this problem has been right in front of us all along: nature.

Our senior members have already hinted at this. Gainesville spoke about the calming effect of animal murals and indoor plants in their hospital. Lüneburg showed us how green roofs and light-filled buildings can create more pleasant environments for students.

But why is this so important?? Attention Restoration Theory explains that being in nature isn’t just relaxing; it’s like hitting the reset button for your brain. Even short periods of exposure to green spaces can reduce stress and improve focus (Ohly et al. 2016; Ackerman 2021). Imagine if our cities weren’t just places to live and work but places that actively supported our mental well-being! A future like that isn’t only about mental health; it’s also about sustainability.

Sustainability: Finding Balance Between Progress and Preservation

Lüneburg, for example, took the brave step of acknowledging its environmental impact and committed to becoming a climate-neutral campus. They didn’t stop at installing solar panels; they rethought their entire approach to energy use. It wasn’t easy, but it was worth it. And the best part? They’re now inspiring other cities to do the same.

Gainesville showed us that sustainability isn’t just about big, flashy projects. Sometimes, it’s the small changes that make the biggest difference. By incorporating biophilic design into their hospital, they created a space that not only looks good but also feels good. It’s a reminder that sustainability and well-being go hand-in-hand.

So, what’s the takeaway here? Sustainability isn’t a one-size-fits-all solution. Each city has its unique challenges and opportunities. The key is to find what works for your community and commit to it. Remember, recovery is a journey, not a destination.

The Future: Building Cities That Heal

So, how do we bring it all together? How do we create cities that are both mentally restorative and environmentally sustainable?

First and foremost, it begins with a shift in mindset.

We need to prioritize green spaces. Parks, gardens, and tree-lined streets shouldn’t be afterthoughts. Instead, they should be central to urban planning. These spaces do more than beautify our cities; they regulate temperatures, improve air quality, and provide places for people to unwind (Mishra and Yu 2022). Think of them as urban detox centers.

Second, urban design needs to be intentional. It’s not enough to just add a few trees to a building and call it a day. We need to create spaces that feel welcoming and inclusive. It’s about designing with empathy in mind!

Of course, biophilic design isn’t without its challenges. Some say adding greenery can raise property values, leading to gentrification, while others worry about high maintenance costs. But these issues don’t outweigh the benefits. Cities can plan green spaces fairly, making them accessible to everyone, not just the wealthy. And while upkeep costs exist, the long-term benefits—better health, cleaner air, and climate protection—make it a smart investment (Beatley 2016).

Finally, cities need to embrace a culture of continuous improvement. Recovery isn’t a one-and-done process. It’s ongoing. No city is perfect, and that’s okay. What’s important is the willingness to adapt and evolve (WHO Regional Office for Europe 2016). Take our friend Rio Grande, for example—it’s working on Projeto Orla, an initiative focused on restoring coastal ecosystems, enhancing public access to waterfronts, and integrating sustainability into urban planning (Brasil 2021).

As we wrap up this session of Ugly Cities Anonymous, let’s take a moment to appreciate how far we’ve come. We’ve admitted the problem, learned from our senior members, and committed to change. That’s a big step.

It’s important to note that recovery is a journey that happens one day at a time. The cities of tomorrow can be places of beauty, sustainability, and mental well-being. They can be places where people feel connected to their communities and the natural world. But it won’t happen overnight.

So, dear participants, let’s keep going. Let’s advocate for greener spaces, more thoughtful design, and sustainable practices. Let’s build cities that inspire, sustain, and truly come alive. Because at the end of the day, we all deserve to live in communities that make us feel at home with nature, with ourselves, and with each other.

References:

Ackerman, Courtney E. “Attention Restoration Theory: A Complete Guide.” PositivePsychology.com, 2021, https://positivepsychology.com/attention-restoration-theory/. Ackerman is a psychologist and writer specializing in positive psychology and mental well-being.

Beatley, Timothy. Handbook of Biophilic City Planning & Design. Island Press, 2016, https://islandpress.org/books/handbook-biophilic-city-planning-design. Beatley is a professor of sustainable urban planning at the University of Virginia, focusing on biophilic cities and urban resilience.

Brasil. Manual do Projeto Orla: Fundamentos e Metodologia. Ministério da Economia, Oct. 2021, https://www.gov.br/economia/pt-br/arquivos/planejamento/arquivos-e-imagens/secretarias/arquivo/spu/publicacoes/081021_pub_projorla_fundamentos.pdf.

Ellis, Cliff. „History of Cities and Urban Planning.“ Art.Net, 2019, http://www.art.net/~hopkins/Don/simcity/manual/history.html. Ellis is a professor of city and regional planning, with expertise in urban history and sustainable design.

GEO-NET Umweltconsulting GmbH. Stadtklimaanalyse Lüneburg. Stadt Lüneburg, Fachbereich Stadtentwicklung, 2019, https://www.hansestadt-lueneburg.de/_Resources/Persistent/0/7/d/2/07d270590a617e27a4236acd35234f864ccf8629/Stadtklimaanalyse_Abschlussbericht.pdf.

“Index Methods and Sources – AARP Livability Index.” AARP, n.d., https://livabilityindex.aarp.org/methods-sources.

McGee, Ben, and A. Marshall-Baker. “Loving Nature from the Inside Out.” HERD Health Environments Research & Design Journal, vol. 8, no. 4, 2015, pp. 115–130. https://doi.org/10.1177/1937586715578644. McGee and Marshall-Baker are researchers in environmental psychology, exploring the impact of biophilic design on health and well-being.

Mishra, Anamika, and Richard Yu. “Urban Planning & Mental Health: How Can We Design Healthier Cities for Our Aging Population to Improve Mental Health Outcomes.” University of Western Ontario Medical Journal, 2022, https://www.academia.edu/97081754/Urban_planning_mental_health?auto=download. Mishra and Yu are researchers in urban health, focusing on how city design impacts mental well-being.

Nnamocha, Marlon. Public Health Group Project Survey. Leuphana University, 2024, https://docs.google.com/forms/d/13XyslAP1dBU8uKNOfTsVLzUiZ0thaiAiOyTsa1o-ERk/viewform?edit_requested=true. Marlon Nnamocha is a student who conducted a public health survey at the Leuphana University Lüneburg.

Opel, Oliver, et al. “Climate-Neutral and Sustainable Campus Leuphana University of Lueneburg.” Energy, vol. 141, 2017, pp. 2628–39, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2017.08.039.

Trenkamp, Oliver. „Libeskind-Audimax in Lüneburg: Prachtbau für die Provinz.“ Spiegel Online, 22 Dec. 2010, www.spiegel.de/lebenundlernen/uni/libeskind-audimax-in-lueneburg-prachtbau-fuer-die-provinz-a-735952.html. Trenkamp is a journalist covering architecture and urban development.

World Health Organization (WHO) Regional Office for Europe. Urban Green Spaces and Health: A Review of Evidence. 2016, https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/345751/WHO-EURO-2016-3352-43111-60341-eng.pdf.

Zühlsdorff, Hanna. “Leuphana Wins the German Sustainability Award 2023.” Leuphana University Lüneburg, 3 Nov. 2023, https://www.leuphana.de/en/university/events/press-releases/single-view/2023/11/03/leuphana-wins-the-german-sustainability-award-2023.html.

Image sources:

Fig.1: OpenAI’s DALL·E. A Creative Illustration of an Urban Recovery Support Group Called ‚Ugly Cities Anonymous. Generated on 12 Jan. 2025.

Fig.2: GEO-NET Umweltconsulting GmbH. Stadtklimaanalyse Lüneburg. Stadt Lüneburg, Fachbereich Stadtentwicklung, 2019, p. 26. https://www.hansestadt-lueneburg.de/_Resources/Persistent/0/7/d/2/07d270590a617e27a4236acd35234f864ccf8629/Stadtklimaanalyse_Abschlussbericht.pdf. Accessed 29 Dec. 2024.

Fig.3: Joergens, Michael. Am Sande in Lüneburg, Germany. CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons. https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/a/a1/L%C3%BCneburg_Am_Sande_012_9319.jpg. Accessed 20 Feb. 2025.

Fig.4: ChatGPT (OpenAI). Time Spent in Green Spaces vs Academic Focus Changes – Leuphana University. Generated on 12 Jan. 2025 in response to user input for project assistance.

Fig.5: ChatGPT (OpenAI). Which of the Following Biophilic Designs Do You Find Most Appealing (Select All That Apply) – Leuphana University. Generated on 12 Jan. 2025 in response to user input for project assistance.

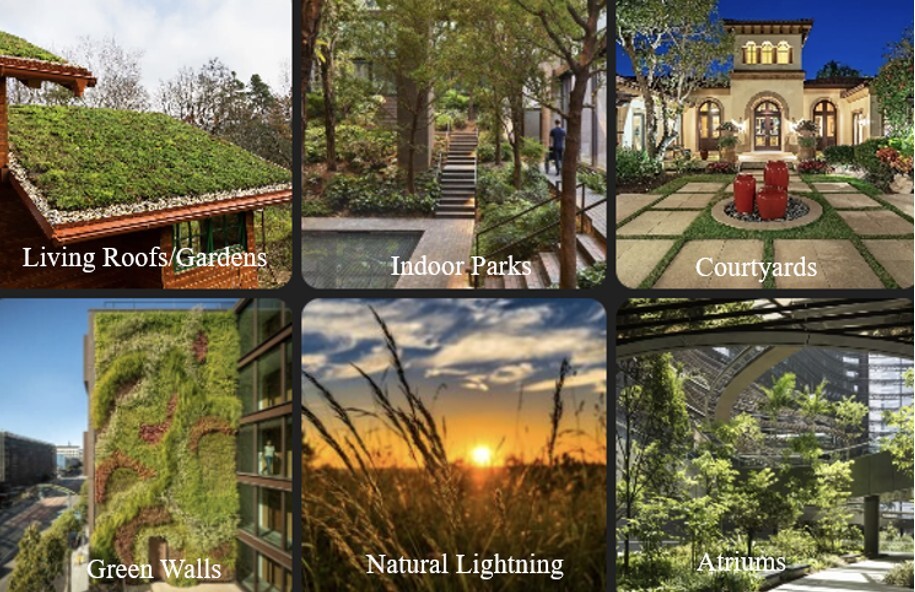

Fig.6: ChatGPT (OpenAI). The Most Appealing Biophilic Design Elements. Generated on 20 Feb. 2025 in response to user input for project assistance.

Fig.7: ChatGPT (OpenAI). Which of the Following Biophilic Designs Do You Find Most Appealing (Select All That Apply) – University of Florida. Generated on 12 Jan. 2025 in response to user input for project assistance.

Fig.8: Thomson, Harshan. Gardens by the Bay, Singapore. CPG Corporation, https://www.cpgcorp.com.sg/images/blog/biophilic-design.jpg. Accessed 16 Jan. 2025.

Fig. 9: OpenAI’s DALL·E. A Modern, The Future with Biophilia. Generated on 12 Jan. 2025.