What part do kids play in building a more sustainable future? Children, like seedlings, require care to develop and grow. Imagine yourself providing your seedling with the daily care and love it needs as you watch it flourish into a plant. What motivates you to do that? Why did you put so much effort into this? Isn’t it possible for it to develop without your care and love? Have you ever asked yourself that?

Just as one should not lose the importance of nature, children should also be considered. As they venture into the world, practical experiences, role models and sustainable education are key to their personal growth and establishment of values. Especially regarding our uncertain future and current environmental issues, children hold the potential to catalyse societal change and take responsibility for shaping sustainable solutions. Children may seem to have little knowledge and power over anything, but they are the ones most vulnerable to change.

Most times, they can provide a perspective that is difficult to take from an adult point of view but is rather unbiased and therefore helpful. Creating a space in which children can learn to understand the world in their own way should be the aim society work for (Klafki, 2005). One can easily mould children's thinking and instil the ideas that will help build a better future. Their social environment steps in at that point to support the process (Belsky et al., 2007). Society's members and structure can create a frame and properly introduce the world to children and children to the world. And this requires a work of heart.

The heart workers

What heart work is about: At Leuphana University in Lüneburg, the seminar “Culture, sustainability, and intercultural communication: An international virtual-exchange project” was established to develop competencies in intercultural communication, collaboration, digital literacy, and sustainable development. Based on the international exchange, students from both participating cities (Lüneburg and Trabzon) worked together in different interest groups. Our team of heart workers consists of five students.

Hey there! We’re Anja, Antonia, Ayşegül, Mahide, Mukaddes, Sarah & Sümeyye. We’re all about sowing awareness for sustainability in young minds. Keep scrolling to find out more about it!

Fun fact about us: What phrase do we associate with sustainability?

Can children be seen as seedlings of society?

Imagine you have the possibility to go back in time.

Back to a moment when you had to decide something very difficult.

Sometimes making decisions is not easy, but we are confronted with them every second of our lives. Under these conditions, we tried to provoke decision-making in our project too. The conditions under which our efforts are implemented are different in specific locations. It depends on where we look, what we look at, and when.

Let’s revisit the image of our plant: The region of Lüneburg in Germany, which is famous for its heath and salt, for instance, has a temperate climate with a mean annual temperature of 9.5 °C and 695 mm of annual precipitation (Landesmedienzentrum Baden-Württemberg, n.d.). Trabzon in Türkiye, an important city for trade on the coast of the Black Sea, on the other hand, belongs to the subtropical climate region and has a mean annual temperature of 14.7 °C and 828 mm annual precipitation (Resmi İstatistikler, n.d.; Trabzon, n.d.). The same plant will grow differently in both locations because of varying environmental conditions. Even the types of plants occurring in each region will be diverse.

Now let’s trade climate, which is easy to measure, for culture, which is not. We cannot measure annual generosity occurrences or smiles per square metre, but we can look at specific practices to find differences. Children’s social environment, society, and culture, with all their norms and traditions, shape a child’s upbringing and education. For instance, the German teaching style is more interactive and relaxed, whereas Turkish schools prefer lecture-style classes and focus on theoretical input, based on our personal experiences. The Heiligengeistschule in Lüneburg is smaller than the Kavalki Elementary School in Trabzon. It is surrounded by more greenery, whereas the school in Trabzon offers a larger courtyard and more space to play. Additionally, the Heiligengeistschule is located right in the city centre of Lüneburg. The Kavalki Elementary School on the other hand, is more distinctly recognised in the city landscape. Both schools conform to the standard national curriculum of their countries.

One, two, three—the best approach for me

We wanted to explore the initial conditions under which children in both Lüneburg and Trabzon are equipped to learn about the environment and sustainability. To do this, we reached out and looked at two schools.

In each city, we implemented a workshop to gain a better understanding of what children from 6 to 10 already know about the term “environment” and what their relationship to it are.

During the workshop the children had to think about their relation to the topic of environment. Because they did not get any further information about the term, they should reflect on their own upon which card would fit the best. Reflecting about whether to take a good or bad decision by choosing the two cards out of 30. But for this activity, there was no right or wrong although they were seeking for the ‘best’ answer.

The children decided based on their own assumptions, perceptions and backgrounds which cards they would choose.

As the kids have different perceptions and knowledge about the topic “environment”, they reacted in different ways to the given task. They were curious and some of them very eager to be able to look at the cards. Some children grabbed them immediately, casting cards away multiple times. Others started with a more hesitant approach and looked around all of them first. Some kids immediately had many ideas in mind, whereas others had to think about what to choose while looking at the pictures.

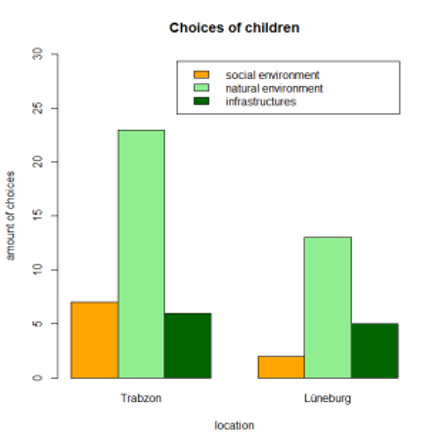

To have a better overview, we decided to divide all choices into three groups each representing a dimension of the environment. There is the category of the social environment (e.g.: family, neighbourhood, and friends), natural environment (e.g.: landscape, fire, animals) and infrastructure (e.g.: solar panels, agriculture, wind turbine).

In the following figure, we tried to bring all the children’s answers together. We compared the choice the children made in Trabzon with those from Lüneburg.

It is really interesting to see that there are differences in all three categories. One can recognise that the children from Lüneburg rely more on natural properties and infrastructures than on social aspects of the term “environment”. In Trabzon, the natural connection was really high too, but the social aspect was considered more than in Lüneburg.

One thing we must highlight is an unequal number of students participated in the workshops in both cities. We had a total number of answers at 56 with different proportions for each city (20 from Lüneburg and 36 from Trabzon) which explain the overall higher number of choices in Trabzon.

Another information we got through the workshop was the difference between the children’s associations regarding their age. We can assume that the higher the age the more reflective the choice was. It seemed that the older children were choosing themes that were closely related or interdependent (e.g.: earthquake and architecture). Younger children, on the other hand, selected cards according to distantly related themes (e.g.: coast and faucet).

As mentioned before, taking decisions is a step people take based on their own assumptions. These assumptions are consequences of our socialisation. This process shapes our way to behave and to decide what is right or wrong in the sense of norms, values, and typical cultural aspects represented in a social group or in society (Bell, 2013). That’s why all the components of a child’s environment are so important. They shape children in their development, just as nutrients support plants in their growth.

Far or close? - Different or the same?

To better compare and understand the results of the two workshops that were placed in two very different cities, we visited the campuses where the workshops took place. Here it is to note that we did not go to a school in Lüneburg as it was not accessible. Therefore, we visited an after-school childcare group where all children were from the same school. At the after-school childcare, children get hot lunches, can do their homework, and play while parents still have to work. So even though the location was not a school, all the children experienced the same curriculum.

In Lüneburg and Trabzon, we scouted for infrastructure that relates to the physical environment, sustainable use of resources and community among the students such as trees, trash bins or a playground.

It was hard to control our inner scientists. We wanted to measure and record everything!

While we know that there is more to a child’s life than their academic education, we cannot visit them at home. Instead, we decided to look around the neighbourhood. We brainstormed what might characterize an environment that promotes sustainability education and then walked around the school surroundings looking through our own lenses.

Regardless, it became evident that the children from Trabzon and Lüneburg are organically exposed to natural environments and experience nature with all their senses every day. Could this be the reason the children from both cities primarily connected physical natural elements more during the card game? The environment of the sites did not extremely differ from one another. So, what is the difference? We understand social external factors help seeds grow and flourish. However, how can a society promote the branches of new knowledge to sprout?

At this point, we understand that culture is defined by values shared by specific communities, countries, or groups of people (Hofstede, 2001). It shapes the way we work and play within society. While it may be simple to say that we just have to become role models for future generations, it may be a bit challenging since a role model may not have this universal image in every culture… not right now at least.

I’m starting with the myself in the mirror

Through the workshop, we saw a window of opportunity for the future of education on sustainable concepts. We saw that environmental topics may need more focus and integration in “mundane” subjects, but also: games, games, games! The interactivity that we experienced during the workshop showed that it sort of is “all fun and games.” Association games, memory cards and the like, hold cognitive and emotional advantages. Being more open to reflexive, collaborative activities have a greater impact than we think. We water the seedlings‘ environment with different forms of knowledge that echo the dynamic and action-oriented nature of sustainability (Kabadayi, 2016). Allow kids to socially interact with one another, recognize patterns, and learn to achieve a goal (High Green Primary School, n.d.). As we grow from rooted seedlings into trunks, sprouting branches, we learn that the more we care and nourish new seeds, the more they can grow and continuously sprout – gaining vibrant leaves.

Insights for the future

Consequently, by cultivating an awareness of the environment and a sense of responsibility for it from a young age, we empower children to actively contribute to the creation of a more sustainable world.

As the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG’s) focus on different dimensions of a sustainable transformation on a global scale, in this case one should take the fourth goal into consideration. This goal fosters qualitative education which serves as a cornerstone for the upbringing of responsible global citizen.

Reflecting on our overall experience, Lüneburg & Trabzon are both on the path to becoming more sustainably driven cities – whether in their urban landscaping or education systems.

The smaller campus, in Lüneburg, embraced by more greenery, and follows a more activity-based learning environment counters the larger campus, more traditional, textbook-based style in Trabzon. While the schools we visited did not completely align with one another, there was still this clear parallel: that the children were aware of sustainability and their environment.

Children should have a fun time while learning about the environment as we did in our workshops. They can learn about nature through experiences such as outdoor activities and trips & culture helps develop a child’s behaviour and way of thinking. So, the concepts of nature, sustainability and environment can be pictured in various ways in children’s minds. Since children can learn many things by observing, we should be attentive to every action we take for the sake of the environment.

As individuals in this society, it’s our duty to help our seedlings flourish and grow into responsible citizens: This way, we can create a better future.

References

Bell, K. (2013, October 7). Socialization definition | Open Education Sociology Dictionary. Open Education Sociology Dictionary. https://sociologydictionary.org/socialization/

Belsky, J., Bakermans-Kranenburg, M. J., & van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2007). For Better and For Worse: Differential Susceptibility to Environmental Influences. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 16(6), 300–304. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8721.2007.00525.x

High Green Primary School (Ed.). (n.d.). Benefits of Playing Card Games with Children. Retrieved 27 August 2023, from https://highgreenprimary.co.uk/just-for-kids/card-games

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s Consequences: Comparing Values, Behaviors, Institutions and Organizations Across Nations. In Behaviour Research and Therapy—BEHAV RES THER (Vol. 41). https://doi.org/10.1016/S0005-7967(02)00184-5

Kabadayi, A. (2016). A Suggested In-service Training Model Based on Turkish Preschool Teachersí Conceptions for Sustainable Development. Journal of Teacher Education for Sustainability, 18(1), 5–15. https://doi.org/10.1515/jtes-2016-0001

Klafki, W. (2005). Allgemeinbildung in der Grundschule und der Bildungsauftrag des Sach- unterrichts. Widerstreit Sachunterricht, 4.

Landesmedienzentrum Baden-Württemberg. (n.d.). Klimadiagramme Deutschland Wendisch Evern. LMZ Geoportal. Retrieved 21 June 2023, from https://geo.lmz-bw.de/klima-d/#/search

Meteoroloji Genel Müdürlüğü. (n.d.). Resmi İstatistikler. T.C. ÇEVRE, ŞEHİRCİLİK VE İKLİM DEĞİŞİKLİĞİ BAKANLIĞI Meteoroloji Genel Müdürlüğü. Retrieved 21 June 2023, from https://www.mgm.gov.tr/veridegerlendirme/il-ve-ilceler-istatistik.aspx?m=TRABZON

THE 17 GOALS | Sustainable Development. (n.d.). Retrieved 27 August 2023, from https://sdgs.un.org/goals

Trabzon. (2023). In Wikipedia. https://de.wikipedia.org/w/index.php? title=Trabzon&oldid=235794703#Klimatabelle

Gib hier deine Überschrift ein

If not indicated differently, all photos were taken or created digitally by members of the group.

Figure 2: https://i.pinimg.com/736x/f2/a0/3d/f2a03dcd7289eef74212d242ef89dd06.jpg, Retrieved 27 August 2023